UW dietetic interns explore sustainable diets

By Lori Tiede

March is National Nutrition Month and the theme for 2023 is “Fuel for the Future,” an invitation by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) encouraging each of us to eat with sustainability in mind. This means choosing foods that are tasty, nourishing, and foods that also protect the environment.

So, what should be on the menu to balance both human and planetary health?

Registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNS), especially those with dual training in dietetics and public health, are equipped to take on these challenging questions.

The Nutritional Sciences Program in the University of Washington School of Public Health trains future professionals who are positioned to work on these issues at a range of scales, from individual to population.

How dietitians in training at UW are considering this question

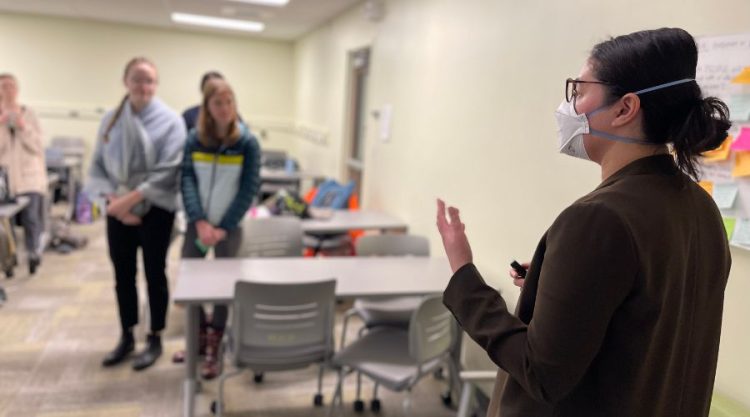

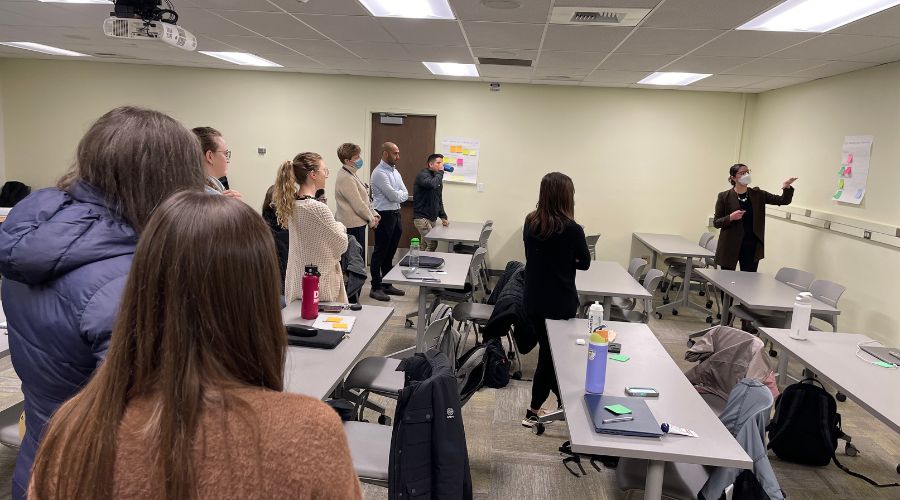

Last month, Anne Lund, an associate teaching professor of nutritional sciences and epidemiology and director of the Graduate Coordinated Program in Dietetics (GCPD) at UW invited colleague Marie Spiker, an assistant professor of nutritional sciences who specializes in sustainable food systems, to speak to her class of second year dietetics interns to discuss the role of nutrition professionals in advising clients on sustainable food choices. In this area, clients might range from individual patients curious about their food choices to food service companies with large-scale institutional purchasing power.

“There isn’t a playbook for RDNs on how to best advise a client if they come to us asking for advice on what’s environmentally the most sustainable dietary pattern,” says Lund. “That’s why having Marie as a resource to our class is invaluable.”

Spiker presented data on food system issues related to food production, consumption, and waste, including considerations related to environmental impact as well as uneven distribution of foods and nutrients which has direct impacts on malnutrition and other health disparities.

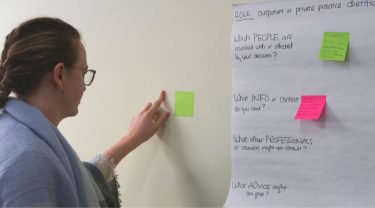

A key activity for the class involved considering how they each might respond in different work scenarios as dietitians to promote planetary health. Rather than jumping right into making recommendations, students were encouraged to consider the people that would be involved with or affected by their decisions, the information and context they would need before making decisions, and the other types of professionals they might consult.

Students noted that the context matters. As future dietitians, they could find themselves providing recommendations that affect an individual client, taking into account individual nutritional needs and household resources and preferences. They could also find themselves providing recommendations to companies or government agencies that have far-reaching implications on farmers, retailers, schools, or workplaces.

Spiker said, “I think this exercise was an exciting opportunity to think about the wide range of career paths open to public health-trained RDNs. I want the students to see that they are each other’s future interprofessional colleagues — some might work in clinical settings, and some might work in government agencies, and they have a lot to learn from each other.”

What is a sustainable eating pattern?

The phrase dietary pattern refers to an individual’s choices in the quantities, proportions, variety, or combination of different foods, nutrients in diets, and the frequency and habits of how they are consumed.

“As an RDN,” said Lund, “our role is to assess the needs and goals of our client, and provide the best information possible to help them reach their goals. Ultimately, though, each person chooses what will work best for them.”

An RDN works with an individual or populations, and makes recommendations based on health needs and goals, factoring in personal preferences, cultural traditions, budget, access, and preventing deficiencies.

Spiker, who is also an RDN also adds, “We want to guide people towards healthy dietary patterns that, ideally, are provided by food systems that are sustainable. Food systems that equitably support people and the planet, including animals and the environment.”

Spiker has shaped AND frameworks on the role of RDNs in sustainable food systems

From 2018-2020, Spiker served as a Healthy and Sustainable Food Systems Fellow with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation. In this role, she led strategic initiatives to grow the capacity of nutrition and dietetics professionals to cultivate sustainable, resilient, and healthy food and water systems.

Her work included convening thought leaders to create a framework for action for how the profession of nutrition and dietetics can amplify its work in this area, co-authoring an updated standards of professional performance for RDNs working in sustainable food systems, evaluating the implementation of a new sustainable food systems curriculum for dietetic interns and students, and developing online learning opportunities to integrate systems thinking in dietetics education.

“There’s this larger movement of public health and healthcare professionals thinking about sustainability issues, like climate change. They are realizing that in addition to addressing the downstream health-related manifestations of these issues, their professions can also play a role in prevention, and building more sustainable systems. It’s really exciting to see nutrition professionals leading many of these conversations, and highlighting critical linkages between food systems and public health,” said Spiker.

Food production trends and outlooks

Some key points Spiker highlights when it comes to food system sustainability globally and in the United States:

- We are producing enough food globally, however it’s unevenly distributed and is not nutrient-rich – We have enough food in terms of calories to feed every person on the planet, however there are significant inequities in how calories and nutrients are distributed, both between and within countries.

- One third of all food globally is lost or wasted– In high-income countries, most food is wasted, while in low and middle-income countries, most is a result of food loss from production or supply chain losses.

- In the U.S., we’ve seen a trend towards agricultural consolidation, with a smaller number of farms feeding a greater number of people.

- The environmental footprint of our food production is high – 11% of greenhouse gas emissions, 34% of global land use, 70% of water withdrawn for human purposes.

- Different foods can vary greatly in their environmental impact, and their relative resource intensity depends on our goals and metrics. For example, while animal sourced foods tend to have higher greenhouse gas emissions, they may also be richer in more bioavailable nutrients. And there are some foods that have a low water footprint on a per-pound basis but a high water footprint on a per-calorie basis. The metrics matter!

Advantages of working with an RDN to support sustainable eating

Whether a certain food choice supports human and planetary health depends on a range of factors, including individual nutritional needs and the broader context of the food system. RDNs can provide guidance that prioritizes and optimizes nutrition and health, with broader sustainability issues in mind.

“In the broader conversations on sustainable food systems,” said Lund, “RDNs have a unique role because we are the only profession credentialed to provide individual-level nutrition advice. So when we’re talking about how different eating patterns can promote sustainability, we really need RDNs to be at the table, as leaders and collaborative partners alongside a whole range of interprofessional experts.”

Learn more about UW graduate programs in nutritional sciences, including the public-health focused Graduate Coordinated Program in Dietetics.

March 8, 2023